- 20 November 2015

REUTERS

REUTERS

Argentina's battered economy is suffering from a number of ills - and the two candidates in Sunday's presidential election run-off vote offer starkly different remedies.

But no matter who wins, there is a high risk of financial chaos in South America's second-largest economy, with many observers feeling that the policies which rescued Argentina from its 2001-02 meltdown, and $100bn (£66bn) debt default, have now outlived their usefulness.

Mauricio Macri, of the conservative Cambiemos (Let's Change) coalition, is the one holding out the possibility of big reforms.

He is currently the front-runner after the surprise result of October's first round of voting, which the governing party's candidate, Daniel Scioli, had been expected to win outright.

In an early indication of what he would do if elected, Mr Macri has pledged to scrap the country's controversial system of price controls that applies to more than 400 supermarket items.

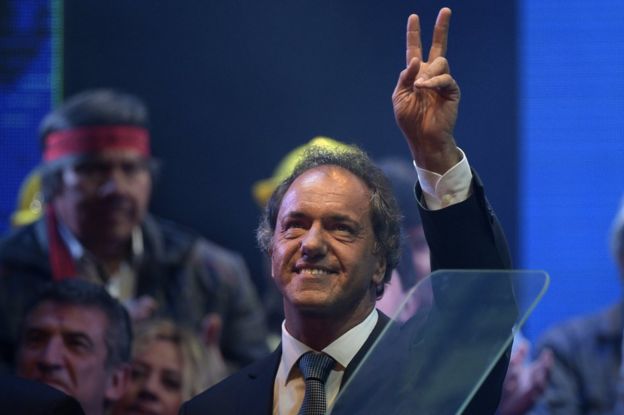

For his part, Mr Scioli is offering the certainty of continuity, even down to maintaining the country's hardline stance in its dispute with US hedge funds that led it to a second debt default last year.

In a recent television interview, he encapsulated the differences between him and Mr Macri in a few words: "I defend the role of the state and he defends the role of the market."

Mr Scioli, the candidate of the left-wing Front for Victory, is standing because outgoing President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner is constitutionally barred from running for a third consecutive term.

For more than 12 years, "Kirchnerism" has been the dominant political force in the country, with President Fernandez succeeding her late husband, Nestor Kirchner, in the top job. Now, however, the end of an era in Argentine politics is at hand.

'Productive paradise'

Mr Scioli's economic policies, as expressed in his campaign speeches, are quite similar to those already in place.

He appears to be pinning his hopes on raising the level of external investment in Argentina, saying he expects to attract $30bn a year in foreign capital.

However, he seems to have no plans to offer potential investors any incentives, saying: "We do not want a fiscal paradise, but rather a productive paradise."

AP

AP

In truth, many foreign firms, from Calvin Klein to British Gas, have been scared off by currency and capital controls that, among other things, have stopped them taking their profits out of the country - not that much money is being made in the current climate.

But Mr Scioli has given no indication that he would reform that system, probably because cash-strapped Argentina is still excluded from borrowing on the international capital markets, and is desperately trying to stop hard currency seeping out of the country.

What he did promise was that he would "gradually" bring down inflation to single-digit levels, "but never at the expense of an adjustment to our social inclusion policies, and with more and better growth instead".

That pledge sidestepped the long-running controversy over the "true" level of inflation in Argentina. The country's statisticians changed their method of calculating price rises last year, because their figures had lost credibility.

However, the revised official index still shows annual inflation at no higher than 14.4%, whereas a panel of experts consulted by Consensus Economics reckons the real rate to be nearly twice as high, at 25.7%.

Out of steam?

Under Kirchnerism, the state has exercised greater control over the economy, including the imposition of heavy taxes on agricultural exports, which helped swell the public coffers and pay for social programmes during the global commodities boom.

Argentina is the second-largest exporter of corn, and the third largest exporter of soybeans in the world, but the market is more precarious than it used to be and the high tariffs have never been popular with farmers.

With that economic model running out of steam and foreign currency reserves still low, it is arguably time for a change. At least, that's what Mr Macri maintains.

AFP

AFP

Not only does Mr Macri want to reduce the state's role in the economy, he is also keen to scrap the country's currency controls, and make it much easier for Argentines to change their local pesos into US dollars - a popular move in a country where hiding dollars under the mattress has traditionally been the preferred way of warding off hard times.

However, such a policy would probably involve a peso devaluation - something which Mr Macri has explicitly ruled out, saying that "I do not think that a devaluation is the solution" - and would certainly require a substantial increase in the central bank's currency reserves.

The only way of doing that in a hurry would be to issue new bonds on the international money markets, which Argentina cannot do while it remains an international pariah because of previous defaults.

That means it would have to strike a deal with US hedge funds that President Fernandez calls "vulture funds". These funds bought "distressed" bonds following Argentina's 2001-02 default, and are continuing to insist on being paid the full face value.

Mr Macri wants to talk to the hedge funds, while Mr Scioli would refuse to.

Contraction fears

While the political debate rages, the Argentine economy has apparently been enjoying a modest pick-up.

The country's official GDP figures are widely seen as being just as unreliable as its inflation data. But Capital Economics believes that the economy returned to growth in the April-to-June period this year, for the first time since 2013.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

"However, this appears to have been due largely to an aggressive loosening of fiscal policy, which will have to be reversed," says Edward Glossop, an emerging markets economist at the research consultancy.

"We expect tighter fiscal and monetary policy to push the economy back into recession next year.

"All told, while the economy may eke out growth of around 0.5% this year, we expect it to contract by 1% next year - although the official figures may not tell you that."

And how is all this affecting ordinary Argentines? Well, according to a recent reportin the country's El Cronista newspaper, about half of all workers in Argentina earn barely more than the minimum wage - that is, they get 6,500 pesos (£453; $692) or less a month.

Whoever wins the presidential election, large numbers of people may not see much improvement any time soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment