As I explained in a previous article about , much medieval and Renaissance European religion art is based on Christian legends which are not found in the Bible. These include stories of the saints, and also stories taken from books of the Bible which are non-canonical, or which are labeled as “apocryphal” and not printed in most Protestant Bibles, although they might be found in Catholic or Orthodox Bibles. In this article, I would like to consider the “Harrowing of Hell” in which Jesus travels into the underworld to rescue the souls imprisoned there in order to lead them to paradise. This is an example of a story which is better known in its many visual representations throughout the medieval churches of Europe than in any written narrative form.

The Biblical basis for the story is scanty indeed. The descent of Jesus into the underworld forms part of the ancient Apostles’ Creed, where Jesus is said to have “gone down to those beneath” (Latin, descendit ad ínferos). There is a Biblical echo of this statement in Ephesians 4:9: “he descended into the lower parts of the earth” (Latin Vulgate, descendit in inferiores partes terrae). The Latin adjective inferus simply means “lower, below, underneath,” as you can see in the English word “inferior.” Yet in ancient Roman culture, the “underneath world” was already regarded as the abode of the dead, so that the plural form of the adjective, inferi, often stood simply for “the dead.” In English, this same Latin root even gives us the word “inferno,” which has lost its sense of “below,” and instead now refers to any kind of terrible “fire,” not limited to the fires of hell.

The fullest written account of the “Harrowing of Hell” is not found in the Bible, however, but in the non-canonical Gospel of Nicodemus, a text which probably dates back in some form to around the 3rd century or even earlier. Here we read how Jesus, after his crucifixion, descended into hell and brought salvation to the souls of the dead who were prisoners there. The story begins with a dialogue between Hades and Satan, who have heard word that Jesus is coming, which prompts a debate about the power of Jesus. Hades is afraid, because he has heard of the miracles Jesus has performed on earth. Satan, on the other hand, has heard that Jesus was crucified as a common criminal; he is certain that they will be able to bind and subdue Jesus when he arrives in their realm.

When Jesus arrives, Hades bids his servants to bolt and lock the doors, but to no avail; Jesus shatters the gates and enters. He seizes Satan and binds him in iron chains, then consigning him into Hades’s keeping until the second coming. Jesus next turns his attention to the patriarchs. He raises up Adam, along with all the prophets and the saints. Together, they all depart up out of Hades, and ascend into Paradise. (You can read a full account in the .) The “Harrowing of Hell” portion of that Gospel was widely circulated in other compilations of religious literature, most notably in the Golden Legend of the lives of the saints, compiled by Jacob of Voragine in the 13th century.

The literary versions of the “Harrowing of Hell” in turn gave rise to many works of art, including the “mystery play” tradition of medieval religious drama. Most commonly, however, people would learn about Jesus’s descent into the underworld from the artwork which decorated the churches and cathedrals of Europe. In the remainder of this article, I would like to look at ten different visual depictions of the story, to see what details we can observe in each artist’s rendering of the scene.

Let’s start with a modern Orthodox icon. In this very simple depiction, Jesus has broken through the doors to hell which he tramples underfoot (notice the locks all broken asunder), and he rescues Adam and Eve. As often, Adam is shown as an old man, while Eve is young. The traditional name for this scene in the Orthodox tradition is the “Anastasis,” the “Raising Up” as you can see written in the icon itself:

Anastasis (modern Greek Orthodox icon) |

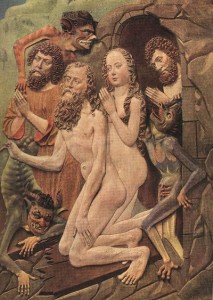

While Adam and Eve are clothed in this icon, they are often shown in the nude, as in this 15th-century wood carving, late 15th century by Veit Stoss from the Mariacki Altarpiece in Cracow, Poland. Notice also here the presence of demons, who are tormenting the dead:

Detail of the High Altar of St Mary, c. 1477-1489

Church of St. Mary, Cracow |

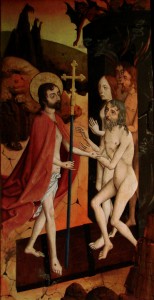

To emphasize that he has only lately been crucified, some depictions emphasize Christ’s wounded hands and feet, as in this 16th-century painting now housed in the Museum of Lille:

16th-century painting (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille) |

While Jesus is often shown trampling the doors to hell underfoot, sometimes he is trampling a demon underfoot, as in this early 14th-century sculpture. Notice also how the scene is paired with the entombment of Christ to the left:

14th-century sculpture (now in the Louvre Museum, Paris) |

Some depictions combine both the door underfoot and the demon, as in this marvelous piece of 15th-century stained glass in the Church of St. Ethelbert, Hessett, Suffolk. Notice the flames licking out from under the door!

Stained glass from Church of St. Ethelbert, 15th-century

Hessett, Suffolk |

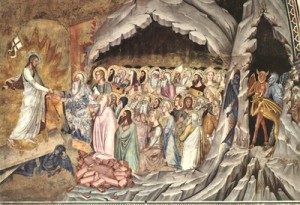

In addition to the demons you might see trampled underfoot or harassing the dead souls, you can also find demons standing off to the side, observing the events, as here in Andrea da Firenze’s famous 14th-century fresco from Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy. Here you can see Jesus rescuing a whole crowd of souls from the underworld:

Fresco by Andrea da Firenze, 14th century

Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy |

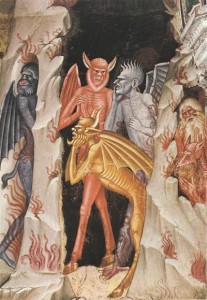

Here is a detailed view of those demons as they watch the proceedings:

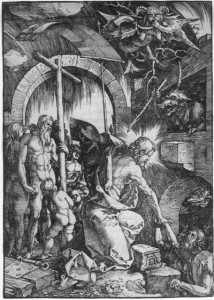

Another character who often figures in representations of the harrowing of hell is the “good thief,” Saint Dismas, who was crucified with Jesus. Jesus promises Dismas that “today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43). Not surprisingly, then, Dismas is also seen journeying with Jesus down into the underworld on their way to paradise. For example, you can see Dismas standing behind Jesus in this woodcut from 1510 by Albrecht Durer:

Woodcut Albrecht Durer, 1510 |

If you look carefully behind Adam and Eve, you can see Dismas bearing the cross in this mosaic from the Church of San Marco in Venice:

Mosaic, Church of San Marco (15th-century)

Venice, Italy |

Sometimes Jesus is also accompanied by angels who battle the demons as he leads the soul out from their captivity, as in this painting by Tintoretto from 1568:

Painting by Tintoretto, 1568 |

As you can see from the quite attractive nude depiction of Eve in Tintoretto’s painting, the story of the Harrowing of Hell provided Renaissance artists a rare opportunity to paint female nudes in a work of religious art. This is carried to extremes, as you can see, in Bronzino’s elaborate crowd scene, painted in 1552 and found in the Refectory of Santa Croce in Florence:

Painting by Bronzino, 1552 |

Refectory of Santa Croce, Florence, Italy ()

You will observe a remarkable contrast if you compare Bronzino’s R-rated scene to the extremely modest Orthodox icon with which we began this survey, an admittedly brief survey which only begins to hint at the wide range of iconographic styles in which this story has been depicted. As Jesus makes this underworld journey in the imaginations of these many artists over the centuries, he joins the ranks of heroes such as Orpheus and Heracles who also journeyed into the realms of the dead, breaking down the doors between that world and this one in order to rescue the souls who have been imprisoned on the other side. Although this is a not a story about Jesus that you will read about in the Bible, it is nevertheless a very famous one, as told both in words and, even more importantly, in images.

No comments:

Post a Comment